|

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth was an elaborate, confusing

structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for

King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur,

creature half man and half bull. That monster was eventually killed by the

hero Theseus. Daedalus had so cunningly made the Labyrinth that he could

barely escape it himself after he had built it.

The Minotaur represents the animal instincts of man, which must be

overcome when on the spiritual path. Ariadne, King Minos' daughter, had fallen in

love with Theseus and, on the advice of Daedalus, gave him a ball of

thread, so he could find his way out of the Labyrinth.

Silver Drachm Coin From Knossos, ca. 300-270

BC, Münzkabinett der Staatlichen Museen, Berlin, Germany

The design above is just one example of a labyrinth. Labyrinths were

depicted in many different patterns.

Some alchemists used the idea of the labyrinth as a metaphor for the

often complicated and bewildering instructions in so many alchemical

texts.

Antoine-Joseph Pernety defines the labyrinth in his Dictionnaire

mytho-hermétique, 1758 as:

The Hermetic Philosophy which uses the fable of

Theseus and the Minotaur, took the opportunity of labyrinth of Crete to

embellish this story, and at the same time it indicates the difficulties

that arise in the operations of the Great Work, by those who want to get

out of the labyrinth when they got into it. One needs Ariadne's thread,

supplied by Daedalus himself, to succeed; that is to say that it is

necessary to be led and directed by a Philosopher who did the work

himself. This is what Morien assures us in his Interview with King Calid.

The labyrinth was a popular illustration in many religious texts, or

paintings, as in the following image:

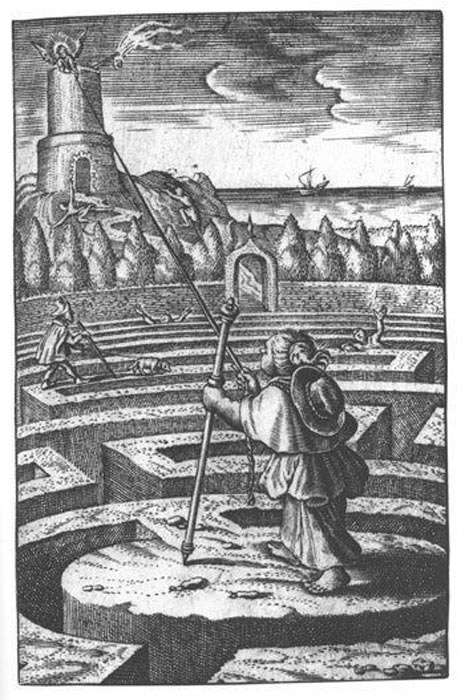

Pia desideria, by Herman Hugo, 1628

This illustration is from an emblem book by the

Jesuit priest Herman Hugo. This is not an alchemical text, but it shows

that the religious interpretation of the labyrinth was well known in

western Europe. It shows Theseus as a pilgrim (the spiritual seeker) in

the middle of the labyrinth (the confusing world), holding the thread of

Ariadne (his soul) who is imprisoned in the tower (the physical body) by

her father the king (the ordinary personality).

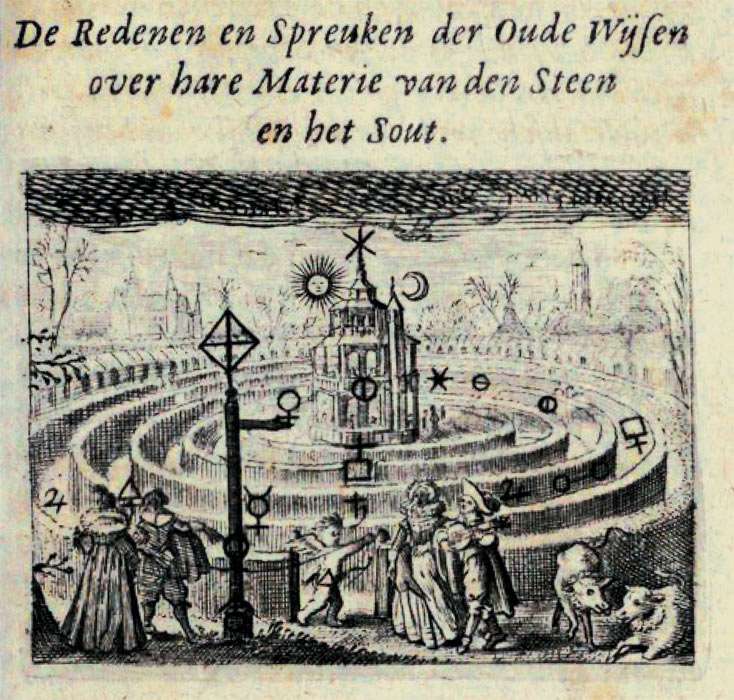

This following illustration is from a Dutch alchemical book, The

Green Lion.

De Groene Leeuw, by Goossen van Vreeswijk,

1674, page 123

The figures in the front wear Spanish outfits, as the book was

published during the era of the Spanish Netherlands. To the right we

have a woman of aristocracy and a man playing a stringed instrument. To

the left, the pair represents Theseus with Ariadne, as there is a string

running from the woman to the putto at the entrance of the labyrinth. In

the middle of the labyrinth is a rotunda, with a a star on top and sun

and moon next to it, symbols for Salt (the body), Sol (the spirit) and

Luna (the soul).

The title above the illustration reads: The reasons and sayings

of the old wise men about their matter of the stone and the salt.

In the text below the illustration, the author writes:

"On page 9 in the Preface of the 12 Keys,

Basilius says that the seed is made out of the stone by the art as such:

It is not necessary to seek the seed in the Elements, because the

seed is not so far from us removed, and the place is nearby, where in

the same it has its home and tavern; and only in the 🜍 and 🜍,

and Salt, namely of the wise, and there is the fame to find. With

these words, he is pointing us the way to go..."

Goossen van Vreeswijk is explaining here that following the teachings

of the ancient adepts serves as the thread of Ariadne that will lead the

alchemist safely in and out the labyrinth of confusing texts, symbols

etc.

As alchemical manuscripts and books multiplied, it became more

confusing for an aspiring alchemist to understand the multitude of

symbols, allegories and descriptions. Thus, it became necessary to have

some kind of guidance, otherwise it was all too easy to give up. Joannes

Agricolae writes in his Treatise on Gold (17th

century) that all these texts were forming a labyrinth of confusion:

"Many a man may well write a process that is

clear enough to an experienced chymist, no matter how obscure it is. To

a beginner, however, it is not only of no use but rather confusing and

damaging - as some of our author's also are - and he gets so mixed up

with them that he can never get out of this labyrinth unless he obtains

an Ariadne's thread. That is why many are induced to abandon the

chymical works altogether, keeping only to the roving vagrants, and

giving the poor patients no matter what, exposing them to mortal danger

- and I know many of them."

Thomas Vaughan writes in his Lumen de Lumine, or a New

Magical Light (1651), about an allegorical vision in which he encounters

a beautiful lady, most likely Nature, about the need for the alchemist

to have thread of Ariadne, identifying Ariadne with the Light of Nature:

"These were her instructions, which were no

sooner delivered but she brought me to a clear, large light; and here I

saw those things which I must not speak of. Having thus discovered all

the parts of that glorious labyrinth, she did lead me out again with her

clue of sunbeams - her light that went shining before us."

|