|

Post stamps might seem mundane, but they are

interesting from different perspectives. For example, the designs and the

subjects they are based on, and that the postal services employ artists

to create drawings and paintings for post stamps. We don't find many post stamps about

alchemy, probably because governments tend to shy away from taking

alchemy seriously. They do commemorate historical alchemists

who became famous for the scientific discoveries that they made. Most alchemists were

also chemists or pharmacists who were knowledgeable about various sciences. This sometimes led to a product that became commercially

successful. Thus what we find portrayed in post stamps are those

alchemists/chemists who are also a national pride.

Aside from looking to the artistic side in the design of

these post stamps, it also gives us the opportunity to learn a little

more about these famous alchemists.

Contents:

Jan Baptist

van Helmont

Johann Friedrich Böttger

Bernard Palissy

Paracelsus

Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe

Arabic Alchemists

Avicenna

Jabir ibn Hayyan

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

................................

Jan Baptist

van Helmont

Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580–1644) was an Flemish alchemist and

physician from Brussels, Belgium. He introduction of the word "gas"

(from the Greek word chaos) into the vocabulary of science. He

was a disciple of the alchemist Paracelsus. Van Helmont viewed

medical alchemy as the only key to curing all diseases and poisons. He

believed in the existence of a universal solvent, Alkahest,

that could extract medical essences out of any being. The Alkahest could

then be used to construct an all-powerful universal medicine

Belgium, 1942, after an Engraving from "Icones

Virorum" by Friedrich Roth-Scholtz (Nuremberg, 1725)

In his masterpiece Ortus medicinae (1648), Van Helmont recounted his

meeting with a mysterious Irish alchemist named Butler. Butler was in

the possession of a 'little stone', lapillus, a wondrous

alchemical medicine that could cure any disease by touching it with the

tip of one’s tongue. Van Helmont was himself given this cure, which, he

says, healed him of a slow poison given by an enemy, who had confessed his

guilt on his deathbed. As he pondered the lapillus and its contents

later on, Van Helmont compared its action with that of viper venom,

which also acted instantly and in very small quantity. Thus he envisaged

snake poison and Butler’s lapillus as polar opposites.

Van Helmont was a

keen reader of Paracelsus, and inherited his framework in regards to

poison. Paracelsus argued that all things contained poison within them,

but poison also had a medicinal side. It was a question on how to

separate the two aspects so that only the medicinal side remained. We

don't know how Paracelsus achieved this with his alchemical preparations,

but it seems similar to present-day homeopathy where the energy of a

physical substance is separated from the substance itself. Being

transferred to a liquid, it becomes a potent medicine.

Van Helmont believed that the alchemical process would obtain the

medical essence as an 'inversion' of the poison. Van Helmond said that

Paracelsus knew how to accomplish the inversion for a medicine called

antimonial tincture of lily. Yet, Van Helmont believed that

Paracelsus did not know that this could be done for all poisonous plants

and animals by using the greater circulated salt solvent, the

universal solvent Alkahest. Indeed, all things lose their poison and

acquire medical power if they are reduced to their primum ens (primal

state of being in which everything is pure and good). Ultimately, the

Alkahest can lead to the creation of the supreme universal medicine.

Johann Friedrich Böttger

Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682-1719) is credited

with discovering the secret of manufacturing European porcelain in 1708

in Germany. Böttger was an alchemist who claimed to be able to make

gold, but failed when forced to do so. Instead he discovered the

secret of making hard porcelain.

In 2010, Germany released a post stamp to commemorate the

300 year anniversary of the establishment of the Meissen factory.

On the stamp we see Johann Friedrich Böttger,

the

son of a mint master from Schleiz. He first learned the pharmacist's trade

at 18 years of age, when he tried to discover and make the philosopher's

stone or tincture that could transmute base metals in gold and provide

external life. He did this in secret, but soon acquired the reputation of an alchemical "gold maker".

In 1701, Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony rescued the young Böttger, who had fled from the court of the king of Prussia, Frederick

I, who had expected that he produce the Goldmachertinktur to

create gold for him as Böttger had boasted he

could. Augustus imprisoned him and tried to force him to reveal the

secret of manufacturing gold. Böttger's transition from alchemist to

potter was orchestrated as an attempt to avoid his execution. In 1704,

impatient with no progress, the monarch ordered scientist Ehrenfried

Walther von Tschirnhaus to oversee the young gold-maker. At first

Böttger had no interest in von Tschirnhaus' own experiments, but with no

results of his own and by then fearing for his life, by September 1707,

he slowly started cooperating. Thinking the deciphering of porcelain's

secrets was his only option left to both satisfy the monarch's greed and

save his own neck, he began cooperating in earnest. Instead of making gold he tried to make porcelain. On

January 15, 1708, Johann Friedrich Böttger and von Tschirnhaus succeeded in producing the first

European hard-paste porcelain in Dresden.

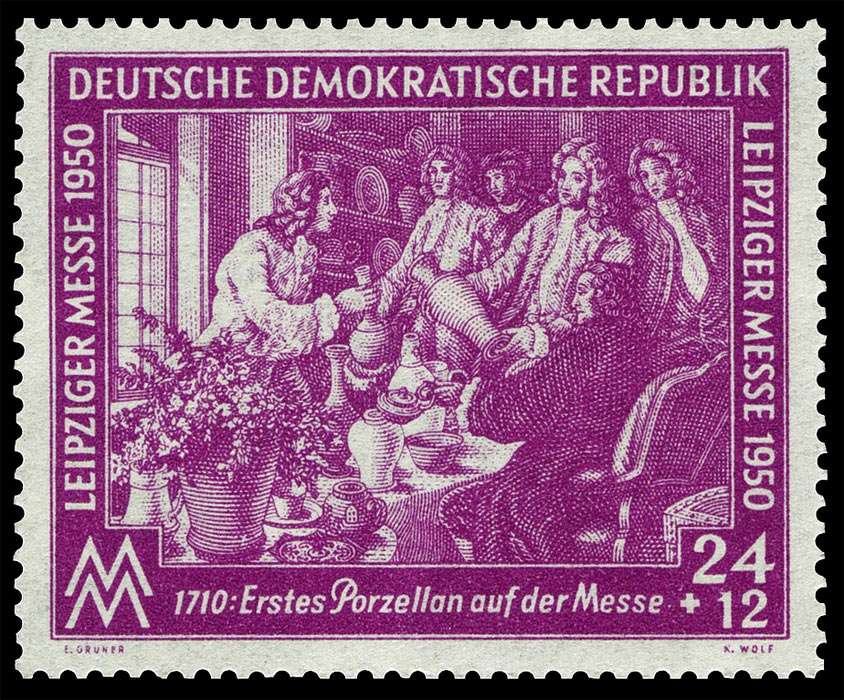

The design of the post stamp is based on a painting by the

German artist Paul Kiessling (1836-1919), where Böttger is showing the

secret of the production of porcelain to the Elector:

In 1950, the Deutsche Demokratische Republik

came out with a post stamp, showing a demonstration of the first Meissen

porcelain at the Easter fair in 1710.

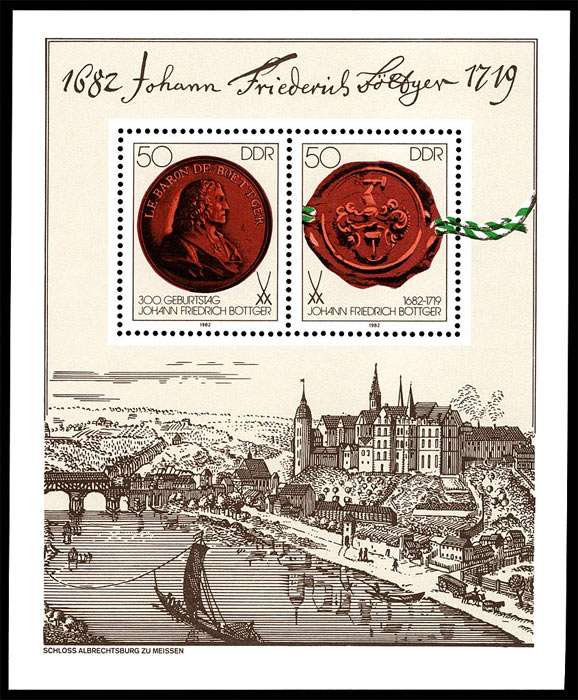

Below is the First Day of Issue of 2X 50 Pfennig

by the Deutsche Demokratische Republik on January 20, 1982. It

commemorates the 300th

birthday of Johann Friedrich Böttger:

The stamps show the only known portrait of Böttger, and his

seal.

The scene is an engraving of the Albrechtsburg Castle in

Meissen, where the first porcelein factory was established.

The portrait of Böttger is based on the only existent portrait

created by François Coudray in 1723. This is on a picture plaque made of

Böttger stoneware kept in the Ducal Museum of Gotha. Böttger stoneware

was a preliminary stage of true porcelain, being hard-fired, brown

stoneware into whose matte or glossy-polished surface decorations could

be cut.

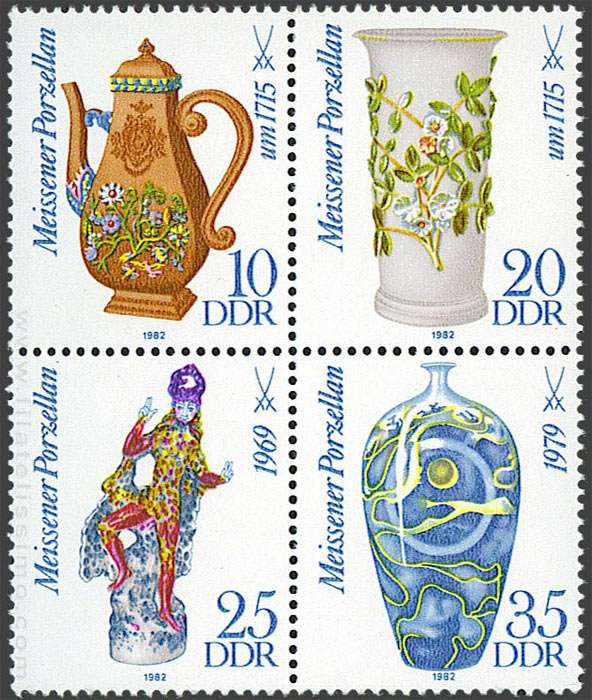

In the same year, 1982, the DDR also created four stamps with Meissen

porcelain to commemorate the 300th

birthday of Johann Friedrich Böttger. They show a coffeepot of 1715, a

mug vase of 1715, a figure of Oberon of 1969, and a vase of 1979.

Right is the coffee pot, displayed in the first stamp, produced in the

Meissen factory in 1710-1730, now in the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin.

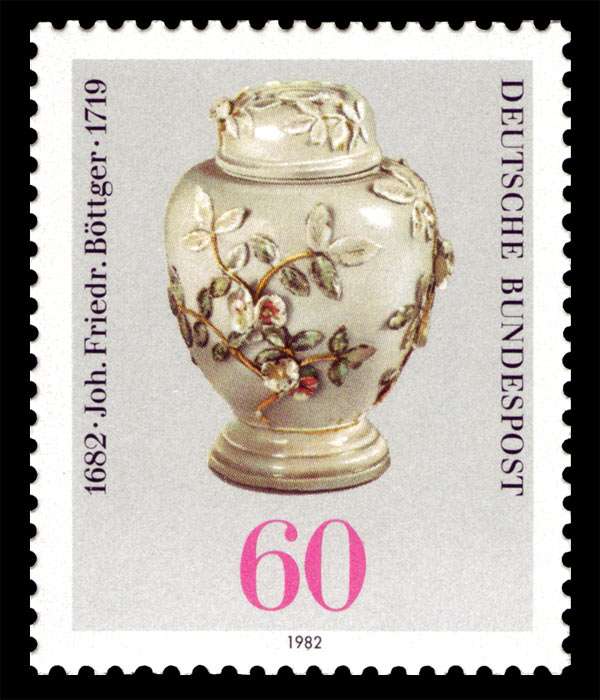

The deutsche Bundespost of the German Democratic Republic also

printed a stamp in 1982 to commemorates the 300th

birthday of Johann Friedrich Böttger, showing a Meissen porcelain piece.

Bernard Palissy

Bernard Palissy (c.1510–c.1589) was a French Huguenot alchemist, potter,

hydraulics engineer and craftsman. He struggled for

sixteen years to imitate Chinese porcelain, but never succeeded. Instead

he created his own type of ceramics, his

so-called "rusticware", typically highly decorated large oval platters

featuring small animals in relief among vegetation, the animals

apparently often being molded from casts taken of dead specimens. As an

alchemist he experimented and developed different colored glazes and

enamels.

Palissy was not only practical alchemist, he was also metaphysical. As

a Paracelsian adept, he subscribed to the Neoplatonic notion of

cosmological harmony between man-microcosm and universe-macrocosm, since

the divine soul of the creator animated all creation. The adept could

anticipate the process of redemption through alchemy, the separation of

pure from impure by fire.

Originally, he made a living by painting and designing. One day, a

wealthy man in the neighborhood of Saintes showed him an earthen cup

from his collection. It was turned and enameled with so much beauty,

that, at the sight of it, Palissy artist was struck dumb with

admiration. The cup probably was Italian porcelain, because no man in

France could make white porcelain or enamels. This spurred Palissy to

search for a way to make enamels as this would provide him with a good

income.

For Palissy, the white glaze of the cup signified the astral spirit

materialized and then merged with the macrocosm in enamel. He began by

making a furnace, and having bought a quantity of earthen pots, and

broken them into fragments, he covered these with various chemical

compounds. He melted them at furnace heat. His hope was, that of all

these mixtures, some one or other might run over the pottery in such a

way as to afford him at least a hint towards the composition of white

enamel, which he had been told was the basis of all others. He labored

for several years without any success, and his family was driven into

poverty.

He experimented with many different types of colored enamels, but

could not produce the white porcelain. He then began to make his own

kind of ceramics, typical dishes ornamented with local flora and fauna

and glazed with many colors. The colored glazes were the result of his

many years of adding different metals to it. Palissy was the first to

make casts from life animals, with which he decorated his enameled

stoneware, from 1555 on. It teems with flora and fauna that he collected

by slogging through the marshes of France. They became popular and were

known as rusticware.

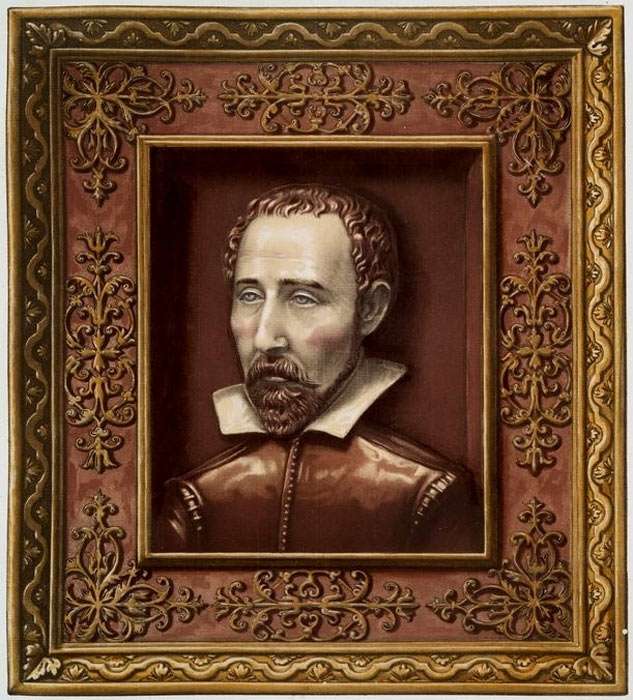

France issued a semi-postal (charity for the benefit of the French

Red Cross) stamp featuring a

portrait of Palissy, designed by French artist Louis-Charles Muller

(1902-1957), engraved by Raoul Serres (1881-1971), and issued

on June 15, 1957.

The post stamp is based on a self-portrait in faïence by

Bernard Palissy himself, held in from the collection of Baron Anthony de

Rothschild in London:

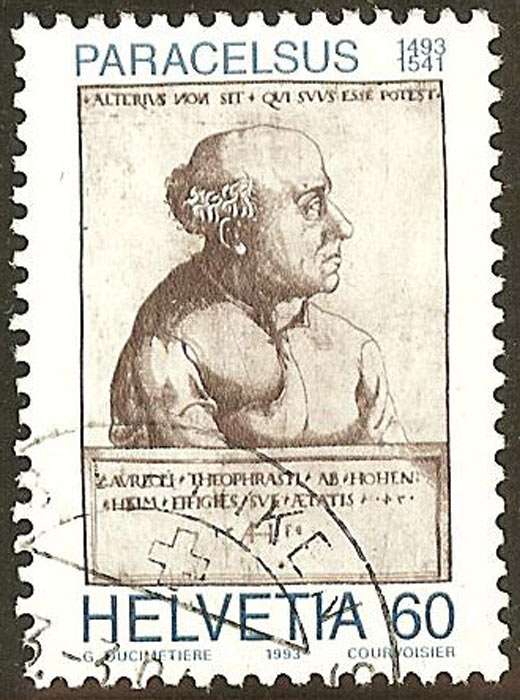

Paracelsus

Philippus

Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim,

better known as Paracelsus (1493–1541), was a Swiss and German alchemist

and physician. Paracelsus sought a universal knowledge that was not

found in books or faculties. For this purpose he traveled all over

Europe. Based on the hermetic idea of Universal Harmony, Paracelsus saw

health and disease as a result of harmony or disharmony in the body.

Disharmony could be cured by (alchemical, or spagyric) medicines.

Early on, he created innumerable enemies by his bold nature and his

innovations, but the value of his mineral medicines was proved by the

cures which he performed. These cures only increased the hatred of his

persecutors, and Paracelsus with characteristic defiance invited the

faculty to a lecture, in which he promised to teach the greatest secret

in medicine. He began by uncovering a dish which contained excrement.

The doctors, indignant at the insult, departed precipitately, Paracelsus

shouting after them: "If you will not hear the mysteries of putrefactive

fermentation, you are unworthy of the name of physicians."

Paracelsus believed that the principles Sulfur, Mercury, and Salt

contained the poisons contributing to all diseases. He saw each disease

as having three separate cures depending on how it was afflicted.

Paracelsus theorized that materials which are poisonous in large doses

may be curative in small doses, which is reminiscent of the later

development of homeopathy by Hahnemann. Overall, Paracelsus' ideas were

quite complex, and not always easy to understand. Being a physician, he

came up with several medical discoveries and highly specific medicines.

Paracelsus came up with many prescriptions and concoctions on his own,

especially for infectious diseases, and the then spreading Black Plague.

He also said that "In all things there is a poison, and there is nothing

without a poison. It depends only upon the dose whether a poison is

poison or not..." He was the first to discover that a poison can be

medicinal in very small doses; or a medicine can be poisonous in large

doses.

Paracelsus proposed that the state of a person's psyche could cure and

cause disease, what we now know as psychosomatic illness.

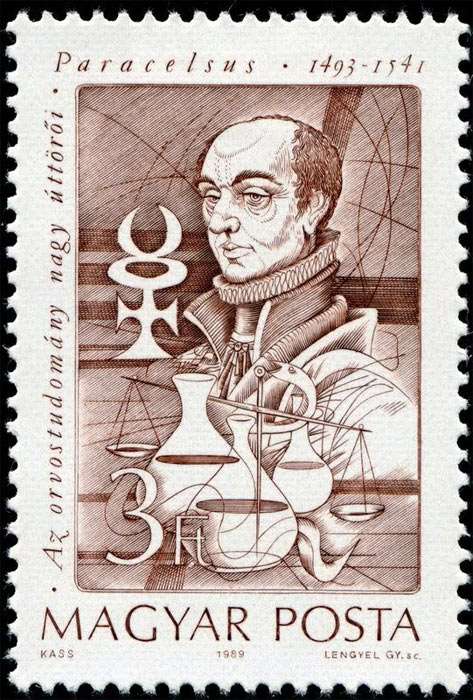

Hungary, 1989

János Kass (1927- ) made this quincentennial

etching of Paracelsus, in 1993. This Hungarian

postage stamp commemorates the 500th anniversary of the birth of

Paracelsus. In this portrait the Hungarian artist emphasizes three

traits of the many-sided Paracelsus: the philosopher, the

pioneer of iatrochemistry (chemical medicine), and the alchemist. In fact, these were the

main aspects that determined the work and writings of Paracelsus as a

physician, a surgeon, and as ethicist as well. This etching is one of

the few recent depictions of the Swiss Renaissance polymath: most of the

approximately three hundred different variants of Paracelsus portraits

were created earlier, in the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Social welfare stamp series 1949

450th

Anniversary of Paracelsus, Austria

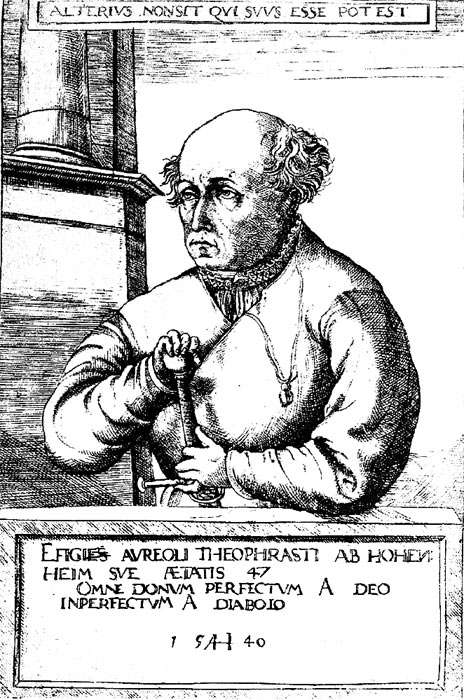

The two stamps above are after a woodcut by A. Hirschvogel, 1540:

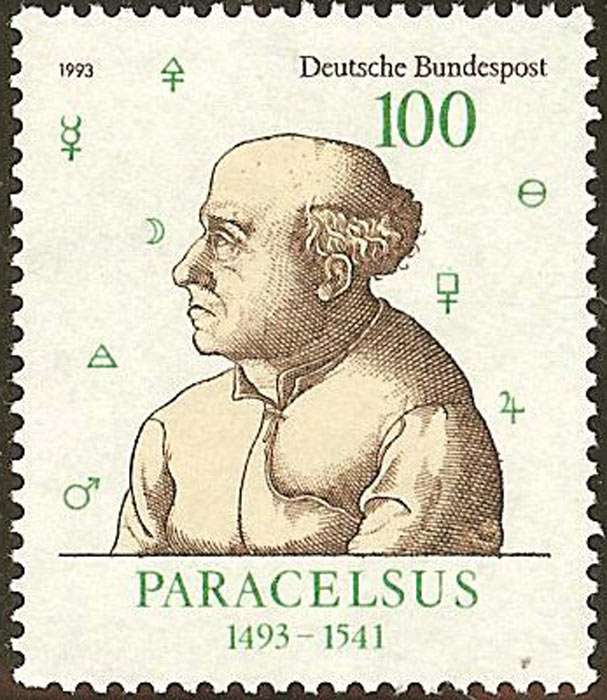

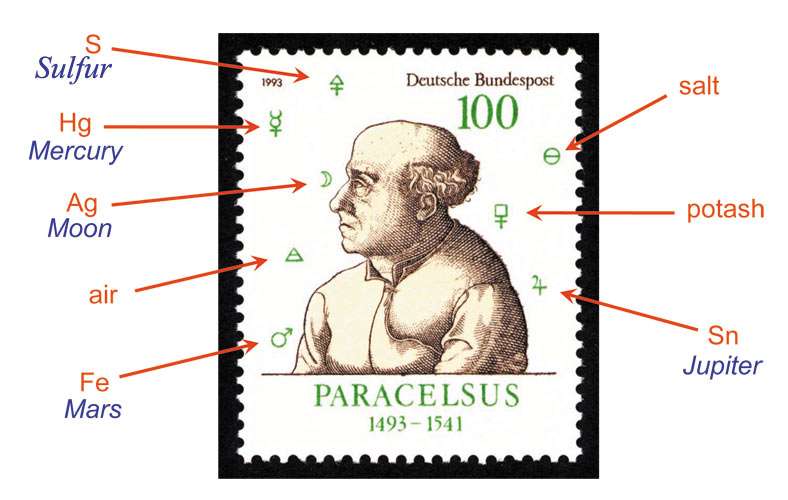

This stamp was issued in Germany on 10 November

1993 to celebrate the 500th

anniversary of Paracelsus’s birth. The stamp features his likeness,

based on a 1538 etching attributed to Augustin Hirschvogel, a German

artist and mathematician known primarily for his etchings. In addition,

the stamp displays (clockwise, starting from the lower left corner) the

alchemical symbols of iron, air, silver, mercury, sulfur, salt, potash,

and tin, all essential tools in the alchemists’ armamentarium.

Interestingly, some of these symbols were also associated with celestial

bodies known at the time, such as Mars (iron), the Moon (silver), and

Jupiter (tin).

Switzerland, 1993; also based on the same

1538 woodcut by Hirschvogel, see below:

![Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim [Paracelsus]. Woodcut by A. Hirschvogel, 1538](media/poststamps/poststamps18b.jpg)

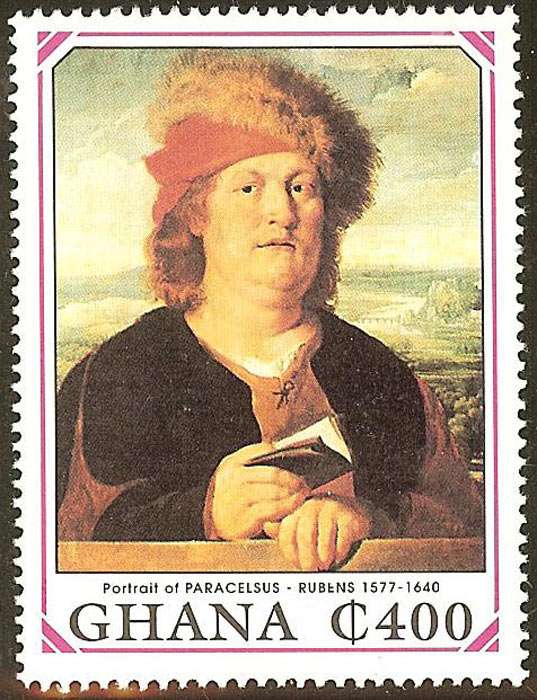

Ghana, 1990

This stamp was part of a series commemorating the 350th

anniversary of Peter Paul Rubens's death.

The image is after a portrait of Paracelsus painted by Peter Paul Rubens

(1577-1640), made in 1678-18, now displayed in Room 52 (Rubens Room) of

the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels:

Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe

The Deutsche Bundespost printed an interesting alchemical post

stamp in 1979, showing Johannes Faust with a Homunculus in a glass vessel,

and Mephistopheles

holding up a mirror in which Faust sees the image of a woman, which

awakens within him a strong erotic desire. It is symbolic for the

ordinary man who is driven by his primitive, animal desires. At his feet

is a magic circle used to conjure up Mephistopheles.

The homunculus first appears by name in alchemical writings

attributed to Paracelsus in his De natura rerum (1537). The

homunculus continued to appear in alchemical writings after Paracelsus'

time. It is a symbol for spiritual regeneration.

Faust is based on a German legend, where the erudite Faust is highly

successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a

blood contract with Mephistopheles at a crossroads, exchanging his soul for unlimited

knowledge and worldly pleasures. The legend is allegedly based on based

on Johann Georg Faust (c.1480–1540), a magician and alchemist probably

from Knittlingen, Württemberg.

The homunculus enters the legend with Goethe's tragic play

Faust. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) is considered to be

the greatest German literary figure.

Faust is considered to be Goethe's greatest work.

Goethe tells us that he began to study alchemy with a Fräulein von

Klettenberg in 1768, in Frankfort to recuperate from an illness. His

interest may have been awakened by a "Universal Medicine," which was

administered by an alchemist friend of von Klettenberg and to which

Goethe credited his cure. At that time he read a number of alchemical

and Hermetic texts and began practical alchemical experiments in his

alchemical laboratory in the attic of his father’s house, directed

toward healing rather than transmutation. These experiments left a

lifelong impression on him, and we know that he continued his "mystico-religious

chemical pursuits" (as he called them). Furthermore, alchemy provided

for Goethe a structure of ideas, which we recurs throughout his

scientific work as well as Faust.

In Goethe's Faust, the Homunculus was unnaturally synthesized by Faust's assistant,

Wagner, in the laboratory. He is a little flame-like man who lives in a

glass vial. Ironically, this creature, who represents the highest

achievement of Enlightenment science, is more human in his desires than

his creator. Rather than sit in a lab all day, Homunculus wants to

experience the world, to evolve, and to achieve what he calls a proper

existence. To this end, he journeys to Greece with Faust and

Mephistopheles for Classical Walpurgis Night, where he rides the

shape-shifting Proteus out into the Aegean Sea, the origin of all

natural life. In the midst of the waves, the creature learns about

nature’s laws and, with fiery passion, he shatters his vial to give his

unnatural body to the natural waters, an act of loving sacrifice that

makes him one with nature. Homunculus’s reconciliation with nature

anticipates Faust’s own reconciliation with the divine order.

There are many post stamps with the head of Goethe. Here are only two

of them: one from the Deutsche Reich 1927, and one from the Deutsche

Post 1949:

Arabic Alchemists

Arabic alchemists were well-versed in laboratory and chemical works,

for many centuries, and made several breakthrough discoveries. They also

held philosophical or hermetic ideas in regard to the substance of

matter. Some upheld the possibility of transmutation of metals, but

others did not. There have been many post stamps issued in the Arabic or

Islamic world to commemorate these alchemists. Here is a selection. Many

of these alchemists were also well versed in other scientific and

philosophical areas.

Avicenna

Ibn Sina, also known as Abu Ali Sina, often known in the West as

Avicenna (c.980–1037). Avicenna was an alchemist, but disputed the

possibility of transmutation. He wrote four works on alchemy. He was

also a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant

physicians, astronomers, thinkers and writers of the Islamic Golden Age,

and the father of early modern medicine. Avicenna was the most

influential philosopher of the pre-modern era.

Iran, 1950

Tunisia, 1980

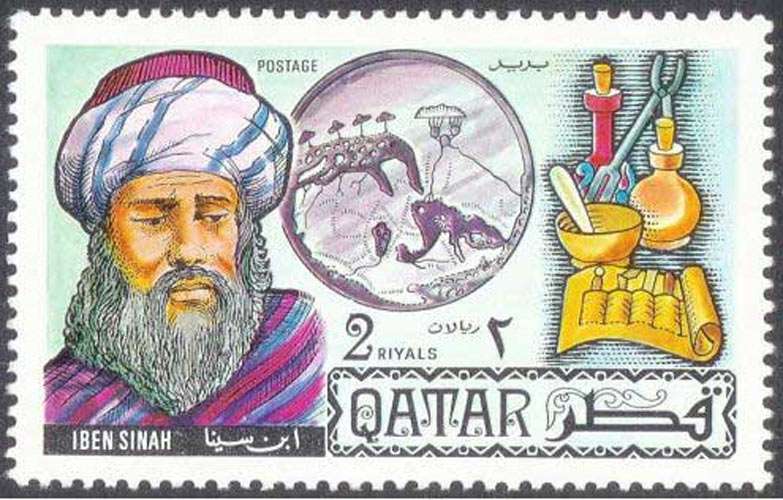

Qatar, 1971

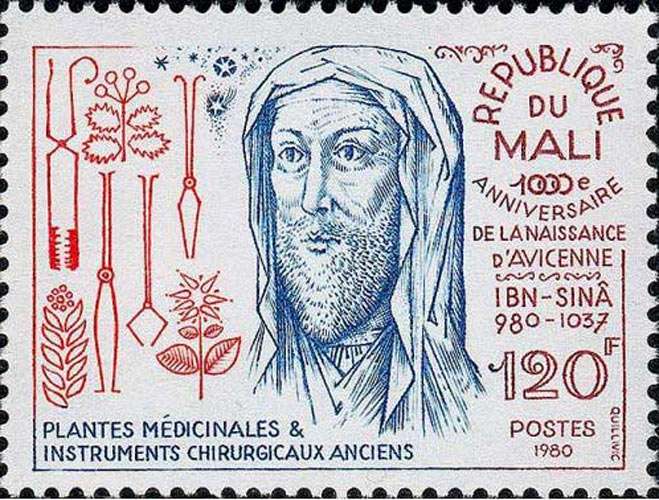

Republic of Mali, 1980

Jabir ibn Hayyan

He was a first century Arabic alchemist who left

a vast corpus of writings, covering a wide range of topics ranging from

cosmology, astronomy and astrology, over medicine, pharmacology, zoology

and botany, to metaphysics, logic, and grammar. He write several books

on alchemy.

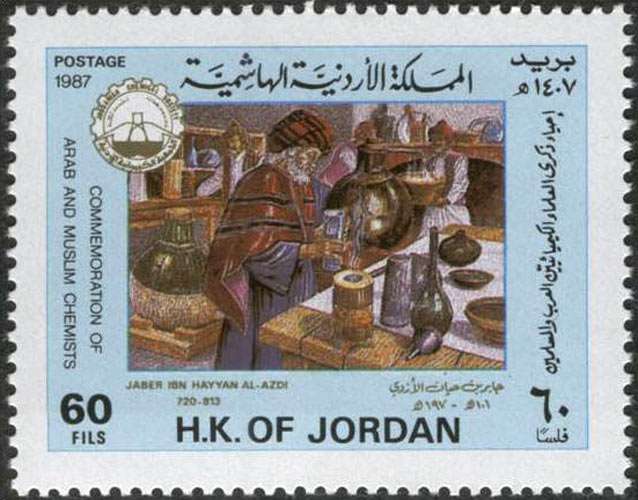

Jordan, 1987

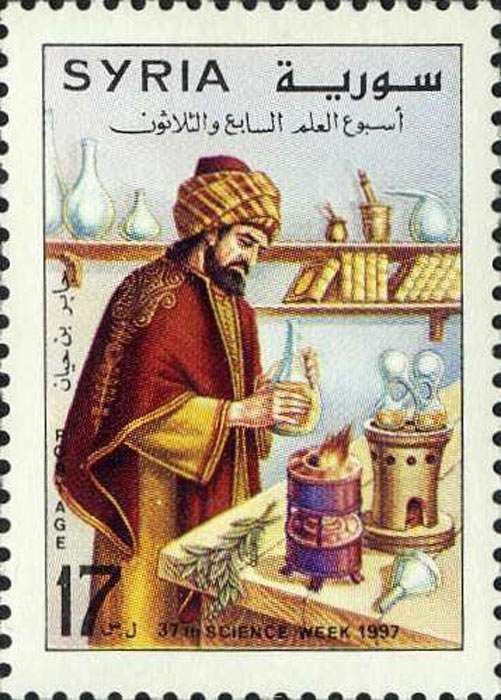

Syria in 1997

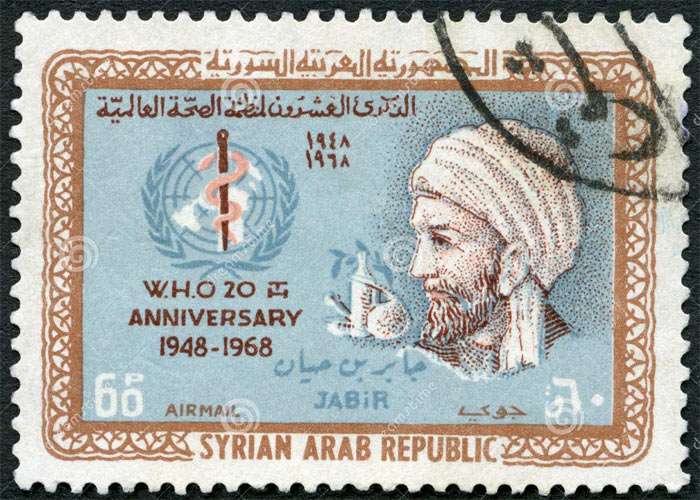

Syria, 1968: shows the World Health Organization

WHO Emblem and Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, also known by his Persian

name Rāzī and by his Latinized name Rhazes (864–925) was a Persian

alchemist, physician, and philosopher. He was widely considered one of the most

important figures in the history of medicine.

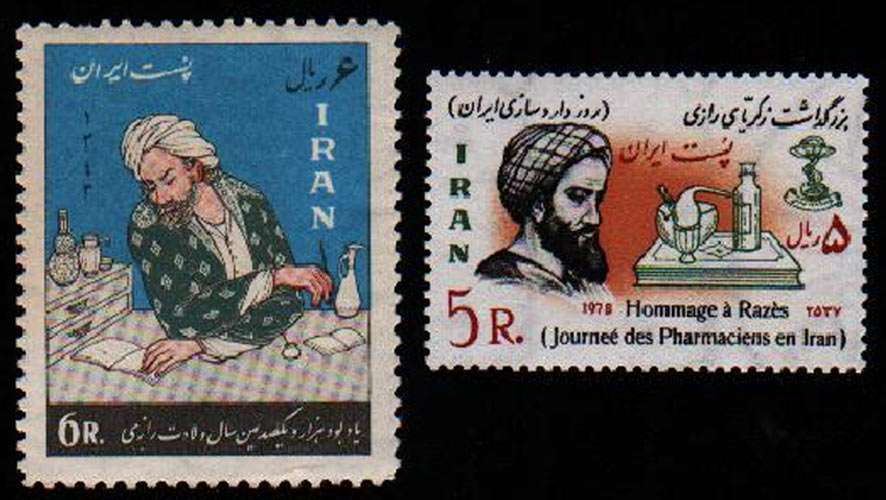

Iran, 1964 and 1968

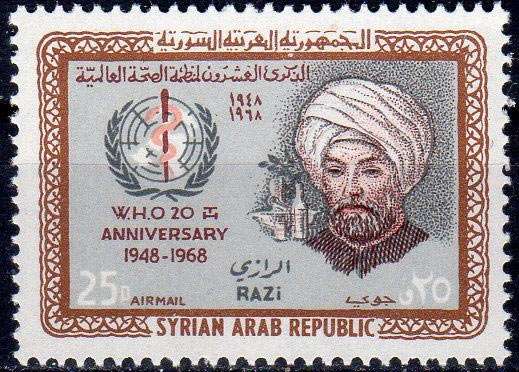

Syria, 1968, with the World Health Organization

WHO Emblem

|