back to The Art of Alchemy index

|

The Catholic Church being a patriarchal institution originally did not pay much attention to Mary, the mother of Jesus. But it had to deal with the persistent pagan goddess worship, which after Christianization adopted Mary as a replacement for their goddess. In the 16th century, Mary devotion really took off. At the same time alchemical manuscripts started flourishing. Alchemy incorporated different esoteric traditions, such as hermeticism and cabbala, and at times Catholic beliefs were fused with alchemical ideas. Alchemists took whatever conceptual and visual materials they required from both pagan and Christian belief-systems and integrated this syncretic mix into their own practical and spiritual alchemical program. There are a couple of alchemical manuscripts that depict the Virgin Mary. In alchemical emblems, Mary is meant to represent something beyond the conventional Christian definitions. She is in many ways more of a Sophia figure. She is the anima mundi, the world soul trapped in the physical world, or the soul of the alchemist trapped in the physical body. This soul needs to be distilled alchemically and purified. Dom Pernety, in his Dictionnaire Mytho-hermetique, defines the alchemical term Virgin as: Moon or mercurial water of the Philosophers after she has been purified of the impure and arsenical sulfur to which she had been married in her mine. Before this purification, she is called the prostitute woman. In the Church we also see the moon associated with the Virgin Mary. In alchemy the Moon or mercurial water is the soul which has been purified and has reached the second stage of the great Work, that is, Albedo or Whiteness. Before the purification, or Albedo, we have the first stage of Nigredo, Blackness, which is the common man, full of the impurities of the lower emotions, and here compared with the prostitute. We will first look at depictions of Mary in alchemical manuscripts, and then have an in depth look at a very intriguing alchemical painting that once hung in a church. Contents: The Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit |

|

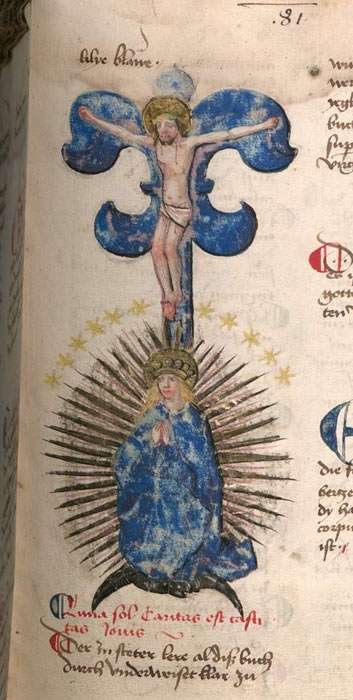

The Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit The Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit (Book of the Holy Trinity) is an early 15th century alchemical treatise, attributed to Frater Ulmannus, a German Franciscan. The treatise describes the alchemical process in terms of Christian mythology. The theme of the book is the analogy of the passion, death and resurrection of the Christ with the alchemical process leading to the lapis philosophorum. The text is one of the most important alchemical works of late medieval Germany. The author of the book didn't see any contrast between the Christian beliefs and the alchemical process. The book contains illustrations of flasks and distillers, recipes and star constellations, hermaphrodites as the union of opposites, together with the familiar Christian figures. The illustrations below are from one of the early hand written editions: Manuscript Cmg 598 from the Bavarian State Library, Munich, and originally published by Franken (Nürnberg?), around 1467.  In the beginning we have an illustrations of the Virgin Mary praying. Alchemists sometimes said that praying was important to obtain the grace of God in order to perform the Great Work all the way to the end.  The Coronation of the Virgin by Christ, God and the Holy Spirit (the dove), surrounded by the four evangelist symbols with their coats of arms. Below a large coat of arms with double-headed eagle.

Left we have Mary praying on the crescent moon, with wavering light light rays behind her. This is a stage where she has not yet reached perfection. Right we have Mary praying on the crescent moon, but this time she is surrounded by twelve stars, and the light beams of her radiance are straight, what means perfection. We don't quite know who the author of Pandora was. It was edited by a physician, Hieronymus Reusner, and published in Basel in 1582. Reusner assigns the authorship to a Franciscan friar with the pseudonym Epimetheus. In Greek mythology, Epimetheus, the brother of Prometheus accepted Pandora as a gift from Zeus, and the title of this alchemical manuscript is: Pandora, That Is, the Noblest Gift of God.

The 18 woodcuts in Pandora are drawn from the earliest German alchemical manuscripts (15th century). They portray distilling apparatus and iconographic representations of alchemical processes. The 14th emblem is based on one of the Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit. The text at the bottom of the image reads Figura Speculi Sancta Trinitatis, or Figure of the mirror of the Holy Trinity. The text to the right is Jesse pater filius et mater, or Jesse father, son and mother. So we have God the father on the right, Christ the son to the left and Maria in the middle. Christ has a text (Latin and German) underneath that identifies him with Sapientia Wysheit, or Wisdom. Maria has Corpus Lyb, or Body. God has Anima Seel, or Soul. The meaning of symbols is not always the same in alchemical manuscripts. They have to be figured out individually. In later works Maria, or a female figure is usually identified with the soul (anima). Here she is the body that needs to be dissolved and distilled (upward motion of her hand), and then sublimated or fixated, symbolized by the dove (the Holy Spirit) flying downwards. Birds flying up and down often appear as symbols for the distillation process. The text underneath the dove reads Terra, or Earth, emphasizing the fixation process. The other text underneath it all reads Die Wijmn der Jungkfrowenn wardt, or She became the bliss of the virgins. This refers to the Assumption of Mary, which is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, and holds that the Virgin Mary "having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory". In alchemical terms this the crowning of the alchemist having completed the Great Work. The Rosarium Philosophorum, or Rosary of the Philosophers is an 18th century English manuscript. The image is from a version in the library of John Ferguson (1838-1916), Regius Professor of Chemistry at the University of Glasgow. The image shows a late version of the Coronation of Mary.

The Rosarium philosophorum is recognized as one of the most important texts of European alchemy. Originally written in the 16th century, it is extensively quoted in later alchemical writings. The Rosarium Philosophorum describes the preparation of the 'stone' in a series of chapters or sections, each having a symbolic picture, most of them accompanied by explanatory verses, and illustrated by parallel passages from the leading authorities, so that the whole forms a 'Rosary' of selected blossoms. Here she is depicted as being crowned by God, Christ and the Holy Spirit. In relation to the alchemical text, she represents the final stage of the Great Work, often symbolized by the crowning of figure, usually a King. Here Mary is the soul, having been completely purified and being accepted into the divine awareness of the self. Furthermore, Mary is also known as the Lady of the Rosary or Queen of the Rosary, and in this sense, it is apt that she appears as last illustration in an alchemical manuscript that is called Rosary of the Philosophers.

This engraving is from Symbola Aureae Mensae duodecim nationum by Michael Maier, 1617. It contains a text, Processus sub forma missae, by Hungarian alchemist and chaplan Melchior Cibinensis, from 1525. Maier was an alchemist and a Lutheran. He illustrated the text of Processus sub forma missae with an image, showing Cibinensis at an altar, and behind him is a vision of the Virgin Mary breastfeeding the infant Jesus. According to alchemists, the Philosopher's Stone had to be nourished with virgin's milk. Here, the child Jesus Christ is equated with the Philosopher's Stone. He is our divine self, that is nourished by our soul (the Virgin). The milk is then the divine spirit. The milk, but also the Virgin is called the mercurial Water of the Philosophers. Philosophorum Praeclara Monita

This is a water color painting after an etching, in Philosophorum Praeclara Monita by Denis Molinier, 1772-3. This alchemical manuscript, held in the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris, contains forty eight allegorical illustrations in color from various earlier works ascribed to George Ripley, Arnaldus de Villa Nova, Ramon Lull, Nicolas Flamel, Eyraeneus Philalethes, Jean de Re and others. Here we have the Virgin Mary standing on the moon, with a hydra at her feet instead of the traditional dragon. Mary is here depicted as the Apocalyptic Woman from the book of revelations, with twelve stars around her head and a dragon at her feet. The dragon, or the hydra, represents the lower emotions or passions that need to be purified. Its tail reaches up into the clouds, signifying the Distillation necessary for the purification. The angel in he clouds with arrow pointing downwards, means the subsequently Fixation or Coagulation. The purified soul needs to be connected again with the physical body. |

|

The Alchemical Virgin at Reims, France In the church of Saint Maurice in Reims, France, there used to hang a remarkable painting, now called The Alchemical Virgin, made by an anonymous painter. A local canon, named Cerf, had already pointed to the esotericism in this work. That's why it was removed from the sanctuary. It was then given to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Reims. In 1907 Henri Jadart, curator of the museums in Reims, said that it had been made by the Jesuits, who left the said church in 1762. He dated the painting to the first half of the 17th century thanks on the one hand to the frame, because it it is the same as from another painting from Reims, the dating of which is not in doubt, and thanks, on the other hand, to its provenance: it was commissioned in all likelihood by the Jesuits of Reims, and it is part of an overall decoration made by them in the 1620s. The Jesuits liked to practice an esoteric Christianity. Not only did some Jesuits practice alchemy, but that there was, in fact, a legitimate space in which they could do so. Although they could not write about it. Some members of the clergy were also members of Masonic lodges and and alchemical societies. Some Jesuits emerged as experts in the occult sciences. For example, in the 17th century there was Athanasius Kircher, a German Jesuit scholar , who devoted two volumes to Hermetic philosophy. About the same period, another Jesuit, Gaspar Schott, under the pseudonym Aspasius Caramvelius, also became known for his knowledge in this field. In any case, the Jesuits were sufficiently interested in alchemy to be accused of being too conciliatory with magicians, astrologers and other occultists when the order was abolished by the French Parliament on August 6, 1762. The Alchemical Virgin is definitely a painting that was intended to incorporate various alchemical concepts in an esoteric Jesuit format. It was probably necessary to have an adept from the order to explain the symbols in a correct way, for as far as he himself knew what the painter had put into his painting. Although we can explain most of them in our own way of thinking, there are clearly some that are left unexplained as to this day. Let's have a detailed look. |

The Alchemical Virgin, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Reims, France

|

The painting must be analyzed in function of a mystical and esoteric syncretism in which alchemy seems to dominate. At first glance, it represents the Blessed Virgin on a crescent moon. Around her head are eight stars. In one hand she holds a receptacle in the form of a cosmic sphere, from which two eagles' heads and the feathers of a peacock protrude. In the other hand she holds a small round temple. A rooster is at the top. At the bottom of the painting is a Greek text: παρΗενος ονοα τεκον : τεκνον μι εχονοα τοκιας. It reads as Parthenos ousa tekon : teknon mè ekousa tokéas. As the semi-colon in Greek is used for a question mark, the text means: Do I have a child being a virgin? A child with no parents. The fact that it was written in Greek means that it was only meant for those scholars who understood Greek. It is indeed a very strange title. The Virgin having a child is still within the teachings of the Catholic Church, but a child with no parents is quite a different thing, and very few would understand it. The child who has no parents is our divine spirit, never born and eternal. When the soul, the Virgin, has been purified, one becomes aware of his divine self.

The Virgin, partly represented in the traditional Catholic way, is alchemically the Moon (Luna), or the mercurial water of the Philosophers, after she has been purified of the impurities of the earth/body. In other words, she is the purified soul of the alchemist. In this painting, Mary is depicted as the Apocalyptic Woman, as seen by the Catholic theologians. The Apocalyptic Woman is a figure described in Chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation. She gives birth to a male child who is threatened by a dragon, identified as the Devil and Satan, who intends to devour the child (identified as Christ) as soon as he is born. Her specific apocalyptic attributes includes a crown of twelve stars and a crescent moon at her feet, while an aura of sun-rays shines about her. These iconographic details have been constant features of the apocalyptic Mary down through the centuries and they have become standardized in Marian iconography. From this earliest iconographic type there developed a closely-related image of Mary as the Immaculate Conception.

The Virgin stands on the Dragon, a well-known alchemical symbol for the unbridled animal passions and lower emotions that need to be tamed.

The Virgin carries a chalice, the alchemical vessel, out of which the peacock's tail emerges with three flowers. The Peacock's Tail is the term used for the stage of the operation when all the colors of the rainbow appear. The three flowers together symbolize the union of the three energies: generative, vital and spirit, into their original undifferentiated state. The three eagles have a similar symbolism, as the eagle is usually the symbol for the sublimated, thus purified matter. The celestial globe is sometimes found in paintings of alchemist's study rooms. It signifies the working of celestial energies on the material work, and thus also on the alchemical process.

The temple is the alchemical athanor, or oven. It is the body of the alchemist; the body taken in its widest sense, including the soul and spirit. The rooster on the roof is the fire in the athanor. The Hermetic Chymists compared their fire to the Rooster, because of its vigor, its activity and its ardor, and consequently gave the name of Rooster to their perfect sulfur in the red stage (Rubedo). There is a plumb line hanging next to temple fastened to a pole that sticks out of one of the windows. This might seem a little weird, but a plumb line is necessary to get a straight upright wall when erecting a building. Symbolically, it means to judge one's actions to see if they 'straight'. It is a symbol of the best of conduct, unequivocal uprightness, and constant integrity required to build a spiritual temple reflective of the best of one’s efforts.

At the foot of the Virgin, we see a scene of a winged globe, a woman holding a flaming heart and a putto with bow and arrow. The putto is Cupido, who is the god of desire, erotic love, attraction and affection. Desire to purify oneself is a first requirement. The woman is the soul, and the flaming heart is the necessary burning love for performing the Great Work. The globe is the physical, be it the physical body or the ordinary personality (dark in color = Nigredo). It becomes winged after the alchemical process has been completed, and the physical matter has been purified or spiritualized.

To the left of the Virgin are two people. The man is holding a caduceus, a rod, a signet ring and a knife against a closed book. The signet ring symbolizes secrecy; it is used to seal a letter, so only the intended addressee can read it. The book is the symbol of book knowledge; it is closest because after book knowledge can only lead you so far, then one has to experience. The caduceus is the symbol for Mercury, so the man probably stands for Hermes Trismegistus. At the same time he is the alchemist himself. The woman might be Nature, as the alchemists say that one should follow Nature, Nature lights the way (with the torch she is holding).

Behind this couple, at the entrance of a temple, stands a woman with a harp and an open book with the number 9 on it. Gold coins fall at her feet. We are dealing here with the temple of Apollo (the lyre is the musical instrument of Apollo). The woman is the Cumae Sybil, the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae, a Greek colony located near Naples, Italy. In the temple she would give oracles. In Virgil's Aeneid is written: "With such words from the shrine the Sybil of Cumae chants her awful riddles and roars from the cave." The Sibyl also acted as a bridge between the worlds of the living and the dead. She guided Aeneas to the underworld. The temple and woman is painted in a dark color, suggestive of the first stage of the Work, Nigredo or Blackness, further enhanced by the Sybil as a guide to the underworld. Also the number 9 on the book is the number of Saturn (the nine squares of the magic square of Saturn). Saturn, also symbol of Nigredo, is also represented by the scythe sticking out of the window above the door. Furthermore, in the Middle Ages, the Cumaean Sibyl was considered a prophet of the birth of Christ, because the fourth of Virgil's Eclogues appears to contain a Messianic prophecy by the Sibyl. In it, she foretells the coming of a savior, whom Christians identified as Jesus. So, the whole setup is an entrance into the dark underworld (of one's subconscious) and the rebirth of the divine self (Apollo or Christ). It is also a reference to the old pagan ways, which, albeit forbidden by the Church, were still held on to and practiced by certain esoteric groups. In this sense, the book the Sybil is holding is the old pagan knowledge. At the feet of the Sybil are golden coins. Gold the symbol for the end product of the alchemical work. The scythe is not only the symbol for Saturn, but it also signifies the death of the old, so the new can be reborn, what is heralded above it on the rooftop of the temple:

On the roof of the temple are two mermen, or tritons, blowing their horns. In mythology, tritons showed up when Venus was born from the foam of the sea, indicating here a rebirth. Here they are announcing the birth of Christ, who is present in the direction they are facing, that is, at the left side of the painting.

The Christ figure is represented as a royal child, seated on the stern of a vessel (the alchemical ship). Christ is holding the rudder, and thus steering the ship in the right direction. Christ is depicted here as a child, because he is the reborn Spirit of man. Christ sits on a heart that radiates; it is the divine radiance of God.

The Christ child is looking to the figure all the way to the left of the ship. He has a lion skin as headdress, and thus he is Hercules. He is situated above all the other crew members, and looking at them while steering the ship. He might represent the Jesuits, guiding the ship of their order. In an esoteric way, the ship is going on a voyage, that is, an initiation (the alchemical process). Hercules performing his twelve labors is an initiatory voyage. The upside down Y below him could be the Greek letter Lambda, and might convey some secret meaning. Hercules is pointing to an old man in a red robe:

The old man has a red robe (suggestive of the third and last alchemical phase Rubedo, or Redness), and he carries an open book. He is the Wise Philosopher. He is pointing to the warrior:

The soldier represent the fighting spirit necessary for the spiritual voyage. He holds a statue of Athena. Athena is the goddess of warfare but also of wisdom; so the warrior is not the brute soldier but he uses wisdom to fight. He is looking towards another old man with an outstretched arm, holding a tree branch with flowers in his other arm. Behind this man stand a king:

The old man and the king are both looking at the Virgin. The old man, holding the tree branch is the Pilgrim. As the king is standing behind Christ, he probably is a symbol for the end of the Great Work, the rebirth of the new king. At the same time he seems to mean something else too, because of his robe and the two numbers 1137 and 1266. They are mentioned again under the winged globe. It is a mystery as to what they mean, nobody has figured it out yet.

A Cyclops (the man has only one eye in the middle of his forehead) is falling into the sea. He probably represents the primordial chaotic realm, or the original primitive personality of the alchemist that has now been thrown overboard and has given way to knowledge and wisdom.

In the mast is Mercury with another figure. He is the divine Spirit of man, high up, having a clear view of the sea, and where the ship is going. I hope this overview has given you an idea how to look at such an

alchemical painting and find the meaning behind the many symbols,

although some Jesuit secrets might be embedded in it that can only be

explained by the Jesuits themselves. |