|

Buddhism is a growing religion in the west, and

it has even become a bit fashionable. It preaches non-violence, offers methods

of meditation and insight in who we are. The Dalai Lama keeps touring the

world spreading Buddhist ideals. When the Dalai Lama visited my town, Woodstock,

NY, there was a non-scheduled, unannounced visit in the village of Woodstock,

around 2000 people showed up for his talk. Buddhism has a lot of good stuff

to offer. You can find a couple of articles based on Buddhist philosophy

in my House of the Sun section. However, over the years I have learned that

the Buddhist monasteries seems to be quite different than what I had preciously

thought. Whenever religion turns into monasteries with hierarchies, titles,

churches, inner and outer circles, financial dealings and political plays,

their members fall too often prey to human weaknesses. There are plenty

of examples that have seen the light in the news media over the past decades.

What I understand about the Buddhist monasteries is the organizational structure

of Tibetan Buddhism which has similar characteristics to any other religious

organization. What I am seeing is that people do not really understand what

Buddhism is about. There is a big difference between the Buddhist traditional

teachings and the Buddhism hierarchical structure in the form of monasteries,

monks, lama's etc. What I will talk about here is my own critical observations

about the Buddhist monasteries, not about the Buddhist teachings. I like

the Buddhist teachings very much. They have a lot to offer and are very

helpful for a lot of people. I certainly have learned a lot from Buddhism,

as well as from Christianity (=teachings of Jesus Christ). I should also

mention that within any religious organization there are also lots of good

people working for the benefit of humanity.

If you are interested in

Buddhism, I believe you should not only read all the good stuff, but also

the dark side of the Buddhist monasteries. Avoiding and ignoring the dark

side is a major stumbling block on the spiritual path. The dark side is

always painful and therefore too often unrecognized. It is important to

recognize where the Buddhist practitioners are failing, and a lesson is

to be drawn for the present and future.

I once read that the reason why

China invaded Tibet (from the spiritual point of view) is that the Buddhist

hierarchical monasteries had become completely stuck, rigid and self serving.

Higher powers intervened and the Buddhist practitioners were forced to move

out into the world. I think a lot of those Buddhist leaders still don't

get it that the structures they created in the old Tibet were clearly wrong

from the spiritual, Buddhist point of view.

I live here in Woodstock,

NY. Up the mountain is the Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, the North American

seat of His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa, head of the Karma Kagyu school

of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded in 1976, the monastery features traditional

teachings as transmitted by Kagyu lineage meditation masters since the 10th

century. Keep in mind the Karmapa term, as I will speak about this later

on. Fourteen years ago I spent about a month up there. At that time only

the main temple building existed (now they are building extensive living

quarters for monks and guests), plus an old hotel building that served as

the housing quarters of about a dozen Americans who live and work on the

property. In the hotel building is also the Buddhist shop and kitchen area

for both Americans and the monks/lamas.

When I was staying on the property,

I helped the Tibetan master painter paint the main temple, which houses

a large statue of Buddha, among smaller other statues and scrolls. I must

say I absolutely adore this main, large shrine room. It is a marvel of art.

Words does not do it justice, you just have to be there. I also spent time

alone in there, in the evenings to meditate. The energy of the room is amazingly

positive, it felt like home to me. I still feel that way. I am convinced

it was built on a power spot, just like the European cathedrals and churches

were.

You have to understand me well: I like the temple building, and

I have nothing against the teachings being given there. But here is what

I find disturbing. The staff, which lived in the hotel building, consists

mainly of people who had become homeless. At the monastery they had a place

to live in return for work on the monastery. Ok, nothing wrong with that,

one needs a place to live. But what I don't like like is the attitude that

they, like so many other people/visitors have towards the monks and lamas.

I first discovered this when helping out in the kitchen. The three lamas

of the monastery and their family members had separate tables, and those

tables had a special elaborate dining set. This fork had to be exactly positioned

this way, and that spoon that way. Like the King of Siam came to visit.

When they came into the dining room, everybody was overly polite to them,

treating them as untouchables. That didn't sit well with me. Lamas and monks,

regardless of their self-proclaimed ranks, are just like everybody else,

human beings on the path to the discovery of the divine self. The Buddhist

teaching say that we are all the same, we are all equal. Isn't it part of

the Buddhist teachings to be detached of the ego and worldly affairs? To

live in simplicity? In stead they are being treated preferentially, what

is mostly the fault of the Westerners. I notice that some people who visit

the Buddhist monastery look at the lamas as if they are semi-gods. This

is a pitfall for most authority figures, like priests, swamis, gurus etc.

The lamas of course like it, it is their power. Being treated like undisputable

masters, they take advantage of their simple minded disciples who they see

as cheap labor. (Their monasteries are built largely by volunteers and with

donated money.)

Here is another thing I stumbled upon. I spoke with

some of the carpenters who were working in the basement. They were hand-making

special cabinets from the finest wood for the private quarters of the lamas.

Well, Buddha gave up his wealth and luxurious living in his palace, and

lived a basic, simple life. Is a wal-mart closet not good enough? I was

shown a door that gave access to the stairway leading to the second floor

where the lamas private quarters where. "Absolutely forbidden to go

there!" I do understand the need for privacy. But you know, I am an

open minded Aquarius for something, so I peeked into the corridor. Maybe

I am too critical, but I was shocked at what I saw, that the corridor has

fancy carpeting and many very nice beveled glass chandeliers. Isn't there

a better way to spend that money? Like helping hungry people in the community?

Meanwhile the staff in the old hotel (where I was staying) were sleeping

in bunk beds, up to six in a bare room. There was only enough warm water

for about three people to take a shower in the morning, the rest got cold.

Do you understand what I am getting at? At one side you have the Westerners

who idolize the Buddhist monks and lamas who still cling to their hierarchical

positions, getting preferential treatment and cashing in on a lot of money

and labor. Their sole existence depends on the donations and money from

teachings, books and publications. Ok, one does need an income, but look

at it as a financial organization. Is that what Buddhism is about? Jesus

threw the Pharisees (who were merchants) out of the temple because "they

don't have a place in the House of the Lord".

Sometimes I think

I am a little bit too critical. But somebody else made the same observations: "The

monks who were granted political asylum in California applied for public

assistance. Lewis, herself a devotee for a time, assisted with the paperwork.

She observed that they continue to receive government checks amounting to

$550 to $700 per month along with Medicare. In addition, the monks reside

rent free in nicely furnished apartments. “They pay no utilities, have free

access to the Internet on computers provided for them, along with fax machines,

free cell and home phones and cable TV. They also receive a monthly payment

from their order, along with contributions and dues from their American

followers. Some devotees eagerly carry out chores for the monks, including

grocery shopping and cleaning their apartments and toilets. These same holy

men, Lewis remarks, “have no problem criticizing Americans for their obsession

with material things." (Friendly Feudalism: The Tibet Myth)

By the way, Buddhist monasteries in Tibet were not unfamiliar with

accumulating wealth. (Ay, here comes the dirty laundry) Until 1959, when

the Dalai Lama last presided over Tibet, most of the arable land was still

organized into manorial estates worked by serfs. These estates were owned

by two social groups: the rich secular landlords and the rich theocratic

lamas. Even a writer sympathetic to the old order allows that “a great deal

of real estate belonged to the monasteries, and most of them amassed great

riches.” Much of the wealth was accumulated “through active participation

in trade, commerce, and money lending.” Drepung monastery in Lhasa was one

of the biggest landowners in the world, with its 185 manors, 25,000 serfs,

300 great pastures, and 16,000 herdsmen. The wealth of the monasteries rested

in the hands of small numbers of high-ranking lamas. Most ordinary monks

lived modestly and had no direct access to great wealth. The Dalai Lama

himself “lived richly in the 1000-room, 14-story Potala Palace.” (Friendly Feudalism

by Michael Parenti)

At present, Buddhist monasteries are still rich. The Karma Kagyu sect

has assets worth over 1.2 Billion dollars. When the Dalai Lama comes to

Los Angeles, he stays in the Presidential Suite at the Huntington Ritz-Carlton

Hotel, which normally rents for $3000 a day.

I used to live in Belgium.

There are plenty of Christian monasteries over there, and many different

fraternities. Most of the fraternities are very active in giving support

to whoever needs it. I once visited the fraters of the Abbey of Norbertynen

in Grimbergen near Brussels. Part of their duty is to go out into the world

and visit elder and sick people to support them in whatever way they can.

I once visited a small abbey church in Brussels. I sat down in the middle

of the rows of seats. there were only two or three other people present.

After a couple of minutes a frater walked up to me asking if I needed to

talk, and if everything was ok. You see, that is true spirituality. In Buddhism,

it is emphasized that there are two things to do on the Buddhist path: meditation

to cultivate the clear, present awareness, AND the Bodhisattva ideal.

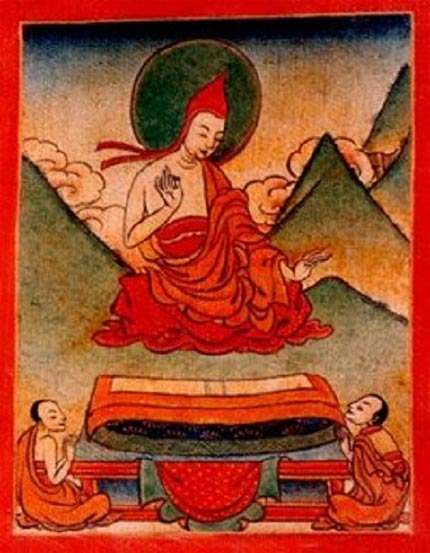

Master Shantideva - 695-743

AD,

the great proponent of the Bodhisattva Ideal and the Middle Way

of Buddhism

The bodhisattva ideal is embodied in the bodhisattva

vow: "May I attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings."

This practically means that one vows not just to attain enlightenment or

Nirvana, but to postpone enjoying that enlightenment fully until all other

beings too have reached liberation. This does not mean that one waits until

he is at the doorstep to enlightenment to help people. Normal people's (and

thus monks and lamas too) own quest for enlightenment is very closely commingled

with works of compassion for others. The Bodhisattva ideal is to actively

help your fellow man in any way you can, on practical level. Within the

Mahayana tradition, compassion for the suffering of others tends to be a

higher priority than liberation for one's self. Or, more properly put, focus

on compassion is understood to be one of the most powerful vehicles to facilitate

liberation, both for others and for one's self. Since, after all, being

concerned with the welfare of others diminishes selfishness, Mahayanists

understand the cultivation of compassion to be one of the best ways towards

the elimination of ego, desire, and suffering for one's self.

I mentioned

the practice of clear, present awareness, the essence of any Buddhist path.

The other day, my wife and I went to visit the Buddhist monastery up the

mountain again. We were talking with one of the staff members, when this

woman introduced us to a lama from another nearby monastery. My wife showed

some pictures of her Tara paintings. I just could not believe my eyes. That

lama didn't connect at all with us, looked briefly at the pictures but didn't

actually see them, and was looking in all directions. His mind was scattered

all over of the place, and he excused himself after less than a minute to

join somebody else. Well, the term lama and its hierarchical position doesn't

mean anything to me. Most ordinary people I know are a hundred times more

focused than he is. And then the woman proceeded to tell us how important

it was the we had met that lama, and it was a connection of profound significance

for our lives.

Well, nobody is perfect, and there are always positive

and negative sides to people and monasteries. I just want to give you some

reflections on Buddhism as a lot of people nowadays feel drawn to it. On

the same visit, my wife gave a woman/visitor a card of one of her Tara painting.

The woman was not only overly polite, but she gave the picture to one of

the monks to pass it on to the head lama to bless it. Why does one need

a blessed picture for? It reminds me of the story in one of Alexandra David-Neel's

books. Alexandra was traveling through Tibet (first part of the nineteen

hundreds) when a procession came by of a high ranking lama bestowing blessing

upon the local people. A hermit (spiritual practitioner) from the mountains

stood next to her. He laughed at the whole procession. Alexandra asked why

he laughed. He told her that people are stupid to believe that the lama

was transferring blessings to them, as he clearly could see (as his spiritual

eye was opened) that the lama could not.

I have given you some of my

personal observations and opinions, but there is more. Remember that I said

to keep in mind the term of Karmapa. It just happens that the monastery

in Woodstock here is the official seat of the Karmapa. You won't hear it

at the monastery, but there is a whole controversy around the Karmapa. But

first I have to explain something else. (the following is based on information

found on other websites).

Tibet in the past centuries was not a happy

country. There were several lineages and monasteries ruling their "territories"

and monopolizing the country's wealth by exacting tribute and labor services

from peasants and herders. This system was similar to how the medieval Catholic

Church exploited peasants in feudal Europe. Tibetan peasants and herders

had little personal freedom. Without the permission of the priests, or lamas,

they could not do anything. They were considered appendages to the monastery.

The peasantry lived in dire poverty while enormous wealth accumulated in

the monasteries and in the Dalai Lama's palace in Lhasa. For hundreds of

years in Tibet, lay followers of each religious school clashed with each

other for control of the government of central Tibet or rule over provincial

areas. Lamas had to defend their monasteries and landholdings from supporters

of the other schools as well as from the central government. (Life in Tibet

before the Chinese invasion was really bad for ordinary people). In 1956

the Dalai Lama, fearing that the Chinese government would soon move on Lhasa,

issued an appeal for gold and jewels to construct another throne for himself.

This, he argued, would help rid Tibet of bad omens'. One hundred and twenty

tons were collected. When the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959, he was preceded

by more than 60 tons of treasure.

Most people think that the Dalai lama

is the head of state of Tibet. But this is not quite true. Tibet has four

main Buddhist sects (lineages): Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug (and a couple

of minor ones). The Dalai lama was the head of only one of them: the Gelug

sect, also know as the Yellow Hats. His lineage was politically powerful,

and he traditionally claims to be the head of state of the whole of Tibet.

The Gelug sect took control over the region of Tibet in the 17th century,

becoming a political center. The other Buddhist sects don't always recognize

the Dalai Lama as their leader.

Where does the idea of "Dalai Lama"

come from? In the thirteenth century, Emperor Kublai Khan created the first

Grand Lama, who was to preside over all the other lamas as might a pope

over his bishops. Several centuries later, the Emperor of China sent an

army into Tibet to support the Grand Lama, an ambitious 25-year-old man,

who then gave himself the title of Dalai (Ocean) Lama, ruler of all Tibet.

His two previous lama “incarnations” were then retroactively recognized

as his predecessors, thereby transforming the 1st Dalai Lama into the 3rd

Dalai Lama. This 1st (or 3rd) Dalai Lama seized monasteries that did not

belong to his sect, and is believed to have destroyed Buddhist writings

that conflicted with his claim to divinity. The Dalai Lama who succeeded

him pursued a self-indulgent life, enjoying many mistresses, partying with

friends, and acting in other ways deemed unfitting for an incarnate deity.

For these transgressions he was murdered by his priests. Within 170 years,

despite their recognized divine status, five Dalai Lamas were killed by

their high priests or other courtiers. For hundreds of years competing Tibetan

Buddhist sects engaged in bitterly violent clashes and summary executions.

In 1660, the 5th Dalai Lama was faced with a rebellion in Tsang province,

the stronghold of the rival Kagyu sect with its high lama known as the Karmapa.

The 5th Dalai Lama called for harsh retribution against the rebels, directing

the Mongol army to obliterate the male and female lines, and the offspring

too. In short, annihilate any traces of them, even their names. In 1792,

many Kagyu monasteries were confiscated and their monks were forcibly converted

to the Gelug sect (the Dalai Lama’s denomination). The Gelug school, known

also as the “Yellow Hats,” showed little tolerance or willingness to mix

their teachings with other Buddhist sects. An eighteenth-century memoir

of a Tibetan general depicts sectarian strife among Buddhists that is as

brutal and bloody as any religious conflict might be. This grim history

remains largely unvisited by present-day followers of Tibetan Buddhism in

the West.

When the Tibetans reorganized themselves in India after the

invasion of the Chinese, the Gelug sect exercised their power once more.

They wanted to make a unified Tibetan community, of course under their control.

The United Party was a plan run by the Dalai Lama's brother Gyalo Thondup

to unite all Tibetans, regardless of their region or religious affiliation,

into a coherent group able to stand together against the Chinese. The most

controversial part of the plan was a scheme to combine the four Buddhist

schools and the Bon religion (governed separately for more than five hundred

years back in Tibet) under a single administration led by the Dalai Lama.

When word of the United Party's religious reform got out in 1964, the exiled

government was unprepared for the angry opposition that leaders of the religious

schools expressed. To them, this unification plan appeared as a thinly disguised

scheme for the exile government to confiscate the monasteries that dozens

of lamas had begun to re-establish in exile with funds they had raised themselves.

You have to remember although the supporters of the Dalai Lama say he is

the religious and political leader of all Tibetans, many Tibetans disagree.

They hold that the four religious schools outside of the Dalai Lama’s own

Gelug governed themselves autonomously back in Tibet; and that they continue

to run their own affairs today, without reference to the authority of the

Dalai Lama.

Another surprising story is that of their involvement with

the CIA and armed conflicts in Tibet occupied by the Chinese. Throughout

the 1960s, the Tibetan exile community was secretly pocketing $1.7 million

a year from the CIA, according to documents released by the State Department

in 1998. Once this fact was publicized, the Dalai Lama’s organization itself

issued a statement admitting that it had received millions of dollars from

the CIA during the 1960s to send armed squads of exiles into Tibet to undermine

the Maoist revolution (remember Buddhism teaches non-violence). The Dalai

Lama's annual payment from the CIA was $186,000. Indian intelligence also

financed both him and other Tibetan exiles. He has refused to say whether

he or his brothers worked for the CIA. The agency has also declined to comment.

I am just stating here the publicly known facts. Personally I think the

present Dalai Lama was too young at that time, and he probably was under

pressure from the other lamas in the exiled Tibetan government. Since then

he has done many good works. Nevertheless, Tibetan authorities preach non-violence,

but send armed exiles into Tibet to fight?

Let's return to that Karmapa

term. Most people know that the the Dalai Lama is traditionally regarded

as the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama. In other words, the same

person keeps on reincarnating. Each time he (as a young boy) is found by

the lamas somewhere in Tibet, and subsequently reinstated as the next Dalai

Lama. This system of repeated reincarnations is the tulku system. A Tulku

is a spiritual teacher, usually the head of a monastery, who chooses to

keep on reincarnating in order to continue to be the leader of the same

monastery.

The first Karmapa: Düsum Khyenpa (1110 - 1193)

It should be noted that the Dalai Lama is not the

only highly placed lama chosen in childhood as a reincarnation. One or another

reincarnate lama or tulku--a spiritual teacher of special purity elected

to be reborn again and again--can be found presiding over most major monasteries.

The tulku system is unique to Tibetan Buddhism. Scores of Tibetan lamas

claim to be reincarnate tulkus.

The very first tulku was a lama known

as the Karmapa who appeared nearly three centuries before the first Dalai

Lama. The Karmapa is leader of a Tibetan Buddhist tradition known as the

Karma Kagyu. The rise of the Gelugpa sect headed by the Dalai Lama led to

a politico-religious rivalry with the Kagyu that has lasted five hundred

years and continues to play itself out within the Tibetan exile community

today. That the Kagyu sect has grown famously, opening some six hundred

new centers around the world in the last thirty-five years, has not helped

the situation.

How did the tulku belief system come about? In the twelfth

century, the first Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa predicted that he would return

to teach his students and manage his monastery in his next lifetime. And

sure enough, when Dusum Khyenpa died, his students located a boy who showed

signs that he was the reincarnation of the Karmapa. The boy was named Karma

Pakshi and when he was old enough, he inherited control over the Karmapa’s

cloister and his activities. From then on, the Karmapa’s monastery was relatively

free of control by local noble families. Being able to choose their own

leader, they became masters of their own destiny. Impressed by the success

of this system, other monasteries copied it as a means to choose their own

top lamas. Thus, over a period of a couple centuries, power shifted in Tibet

from landowning families to the lamas who managed the most powerful monasteries.

The most revered tulkus attracted donations and students, developing monastic

empires and political power of their own. As tulkus became major political

leaders in their regions, lama-rule in Tibet reached its apex. In the late

fourteenth century, nearly three centuries after the first Karmapa, the

Dalai Lamas would appear.

The Tulku system was invented by the monasteries

to be able to control their religious/political power by themselves. Outsiders

might think that spiritual masters were always located according to set

procedures laid down to ensure the accuracy of the result—that the child

located would be the genuine reincarnation of the dead master, as in the

scene from the movie Kundun. But in Tibetan history, tulku searches were

not always conducted in such a pure way. Reincarnating lamas inherited great

wealth and power from their predecessors and thus became the center of many

political disputes. Tulkus were often recognized based on non-religious

factors. Sometimes monastic officials wanted a child from a powerful local

noble family to give their cloister more political clout. Other times, they

wanted a child from a lower-class family that would have little leverage

to influence the child’s upbringing. In yet other situations, the desires

of the monastic officials took second place to external politics. A local

warlord, the Chinese emperor or even the Dalai Lama’s government in Lhasa

might try to impose its choice of tulku on a monastery for political reasons.

Only the strongest monastic administrations had the ability to resist such

external pressures, and the Karmapa’s monastery was one of these. Sixteen

Karmapas were recognized by the Karmapa’s own monastery and without participation

from outsiders. Only in one instance, when the sixteenth Karmapa was recognized

in the 1920s, did the Tibetan government of the thirteenth Dalai Lama try

to intervene in choosing a Karmapa. In that case the government ultimately

had to back down.

Soon after the 16th Karmapa arrived in Sikkim, India,

in 1959,

constructions of his Rumtek Monastery began. It served as his

seat outside Tibet and quickly became well known throughout the Himalayan

region because of the Himalayan peoples' devotion to the Karmapa. In contrast

to the Karmapa, most other lamas who fled from China found themselves in

a weak position.

In an effort to unify the Tibetan exiles and thereby

strengthen their opposition against the Chinese government, the Dalai Lama

and his brother Thondrup in 1962 formulated and began to implement a policy

of political, ethnic, and spiritual unity for all Tibetan exiles. Lamas

belonging to the three lineages outside the Gelugpa School supported the

political aspect of this policy but were quite suspicious of its call for

spiritual unity. They feared this would end the traditional independence

of their lineages. Therefore, Nyingma and Kagyu lamas encouraged the Karmapa

to lead a resistance to the Tibetan Government in Exile's policy for spiritual

unity.

For almost two decades the 16th Karmapa (who died in 1981)

actively opposed the Dalai Lama's spiritual unification policy until his

death. This put extreme pressure on the Dalai Lama because over 13 large

Tibetan Resettlements Centers in the Himalayan region unanimously supported

the Karmapa. In addition, all the high Nyingma and Kagyu lamas followed

the Karmapa without question because of his leadership and of the Karma

Kagyu and because generations of repression of the Karma Kagyu by the Dalai

Lama's government left the Karma Kagyu disgusted with it.

Then the sixteenth

Karmapa died in 1981. The sixteenth Karmapa had built the monastery of Rumtek

in the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Sikkim, which became a state of India in

1975. After his death, the four regents in charge of looking for his reincarnation

had trouble finding the boy who would take over. While the Tibetan Buddhist

lineages use various methods for finding the reincarnation of a high lama,

the Karmapa traditionally wrote a letter before he died indicating where

his successor would be found. Eventually in 1992 one of the regents, Tai

Situ Rinpoche, produced a letter which he said had been hidden in a talisman

given to him by the 16th Karmapa. But when regent Shamar Rinpoche saw it

he claimed it was forged, alleging the script was "100 percent Tai

Situ's handwriting".

Shamar, though, was in a minority. His call

for a forensic test of the letter was overridden and the search went ahead.

Tai Situ brought in the Dalai Lama to officially bless the recognition,

which critics say is an unusual step as the Dalai Lama is head of the Gelukpa

Buddhist lineage, not the Karma Kagyu. Their boy was also supported by,

surprisingly, the Chinese government as well. Back in Sikkim, with the help

of local state police and paramilitary forces, these lamas and their followers

took over Rumtek monastery in 1993. The Indian government however does not

allow him to be in the Rumtek monastery, so he lives in Dharamsala (the

headquarters of the Dalai Lama). In 1994, another prominent lama, the nephew

of the deceased Karmapa and the lama whose predecessors had chosen the highest

number of Karmapas in past centuries installed his own boy (Trinlay Thaye

Dorje) in India. Thus began a struggle over the identity of the seventeenth

Karmapa that continues to the present day.

Rhumtek monastery

Thus there are now two Karmapas: Ogyen (or Urgyen)

Trinley Dorje who was approved by the Dalai Lama, and Trinlay Thaye Dorje

who is recognized by Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche, second to the Karmapa in the

Karma Kagyu Lineage. So who is the real one? That has confused a lot of

Tibetan Buddhists. The result is that some monasteries and Buddhist centers

(about 600) take Trinlay Thaye Dorje as their Karmapa, and others (about

200) take Ogyen Trinley Dorje as their Karmapa.

So now we have two Karmapas,

a division in the Kagyu sect, violent clashes between the two and a lot

of confusion. What is so important about the Rumtek monastery that is was

taken over by force? Is it because that besides vast material wealth, the

lama that finally inherits Rumtek inherits the most sacred object of the

Kagyu sect: a magic black hat. Ah, now it gets interesting, who wouldn't

want a magic object? As the story goes, the 1st Karmapa spent many years

meditating in a cave. Ten thousand female deities came to congratulate him

and each offered a strand of hair. These strands were woven into a black

hat. It is said that unless held in the hand or kept in a box the Black

Hat will fly away. It is said that when the Karmapa places it on his head,

he has to hold it down with his hand to prevent it flying away.

The 16th Karmapa, who died in 1981

There is a rumor going around that the Ogyen Trinley

Dorje left Tibet/China to take the black hat and other belongings of the

16th Karmapa and return to Tibet/China. It is a bit strange why he left

Tibet. He himself claims that he was living in a golden cage (he was living

a good life as the Chinese were treating him well. By all accounts, the

14-year-old led a rather pampered existence in Tibet complete with toys,

chauffeured limousines and trips through China. Trinley Dorje was particularly

valuable to the Chinese bureaucracy, as he was the only high lama recognized

by both the Dalai Lama and Beijing.) He jumped out of his window into a

waiting car and with two experienced drivers, his sister and several other

passengers sped off to the border of Nepal. Details of the journey into

Nepal then onto New Delhi vary widely—many include a romantic ride on horseback,

some the more prosaic use of public transport and others the possibility

that he and his party simply caught commercial airline flights from the

Nepalese city of Pokhara. How the car managed to evade Chinese security

within Tibet, how he and his group were able to cross two international

borders without passports or papers; and where he obtained a car and the

necessary money in the first place; all of this is left somewhat hazy.

One might think that Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the Karmapa chosen by the

Dalai Lama might have an easy path. But it turns out different. Ogyen Trinley

Dorje was born and grew up in Tibet, and was also approved to be the Karmapa

by the Chinese government. So the Indian government is very suspicious why

he fled Tibet and came to India. Since his journey into exile, the lama

has only been given permission by the Indian authorities to travel on pilgrimages

to holy places. And he is banned from traveling to his goal, Rumtek, in

Sikkim, a small Himalayan state under Indian administration but claimed

by China.

More problems: In 2003 a bitter legal contest over the assets

of Rumtek monastery has resulted in an unfavorable verdict. An Indian court

in Sikkim ruled that the assets of Rumtek belong to the Karmapa Charitable

Trust, set up by the late 16th Karmapa. The trustees support Thaye Dorje,

whom they say has the right to take over the monastery. Urgyen Trinley's

followers, whose monks currently occupy the premises, made an appeal to

the Supreme Court which they lost.

Well, if by now you have lost track

of what it is all about, look at the historical Buddha. He left his wealth,

political power and palace, and lived in utter simplicity.

|